* Bring your coffee this is a long read.

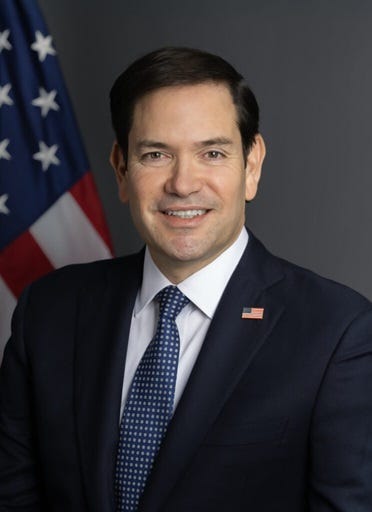

On Thursday, Marco Rubio, the new U.S. Secretary of State, gave a wide-ranging, hour-long interview that offers a revealing glimpse into the Trump 2.0 foreign policy agenda—and how it’s set to unfold.

From reviving the idea of acquiring Greenland and asserting control over the Panama Canal to countering China’s rise and even entertaining the prospect of Canada as the 51st state, the administration’s approach is nothing if not unconventional.

Unlike my three-part breakdown of Antony Blinken’s last interview as Secretary of State (part 1, part 2, part 3), I opted to keep this one cohesive. The themes Rubio touched on are deeply intertwined and separating them would dilute the overarching narrative—a foreign policy rooted in disruption, centralized decision-making, and transactional global engagements.

Rubio’s stance may shift as he grows into the role, but this interview already lays out the contours of what’s coming. And if his words are any indication, U.S. diplomacy is in for a turbulent ride.

The Rubio - Trump Dynamic and the Role of the Department of State

Earlier, I covered Marco Rubio’s rise through the Republican Party, his initial opposition to Donald Trump in the 2016 primaries, and his eventual pivot to supporting Trump, his pragmatic approach to politics and his involvement in foreign policy as an elected official in congress.

I had predicted that his role as Secretary of State would feature limited autonomy, and revolve around execution of policy dictated from the White House, implementing Trump’s foreign policy agenda rather than advising on it. This interview corroborates that perspective to a considerable degree.

As the interview progressed, he emphasized either directly or indirectly that Trump was the primary driver of foreign policy; Rubio praised Trump’s confrontational style, highlighting its effectiveness and endorsing the notion that Trump’s methods—not traditional U.S. foreign policy—are the key to safeguarding American interests abroad. This built on the same pattern of the Colombia U.S. deportation dispute, where the dynamic clearly revolved around heavily centralized decision making at the White House and execution by the Department of State, whether on tariffs or broader policy.

Rubio also emphasized that the President is highly accessible, both to officials within the U.S. and international officials, from which we can deduce a few important issues. First, is that as a department focused primarily and potentially exclusively on execution, with its advisory role minimized, it is no longer an effective diplomatic channel for foreign governments. The understanding that the department has little sway over the President’s decisions means that it doesn’t matter if you convince its officials of your position because they do not have the president’s ear.

Second, by indicating the President is open to direct communication, he incentivizes foreign governments to prioritize communication with the White House over the Department of State sidelining its role as a diplomatic organization. Adding weight to this probability is when he described his vision for U.S.- Russia and U.S. China engagements, where he emphasizes that decisions on those matters would revolve around the dynamics between the respective heads of state, highlighting the centralized decision making model adopted by the current administration.

Essentially, from what Rubio implied about his and the Department’s role, the institution will be more of an echo chamber for the president’s policies than an advisor capable of reining in the more outlandish ideas on foreign policy approaches.

When asked about how he sees opposing views within the Department of State and how he would handle them, he emphasized that the job of the department is to execute the president’s foreign policy, which is not wrong in and of itself but is incomplete because a critical role of this Department and its equivalents is leveraging its expertise and institutional memory to advise the head of state on foreign policy decisions. This role is entirely absent from Rubio’s assessment.

This, in part, can be attributed to Trump’s leadership style and his reasons for choosing Rubio and other candidates for high level positions within government. Trump’s priorities revolved around having loyal supporters in key positions, and this was no exception. Throughout this interview, the new Secretary of State made sure this loyalty was highly visible, a decision that will likely help him consolidate his role in the administration.

Redefining Power, Abandoning Influence?

Rubio stated that under Donald Trump, U.S. foreign policy is ‘returning’ to pragmatism, and while he briefly paid lip service to ‘principles,’ he shortly thereafter all but said that they would not factor into the decision making equation.

While the U.S. is not regarded as a global protector of human rights and international law outside its own borders, it has over the years elevated the use of these principles and laws to an artform in pressuring governments to align with its interests and policies. It has wielded them effectively as a matter of policy and consistently upheld them -at least theoretically- when engaging in negotiations.

When the Secretary of State says outright that these issues are no longer a primary concern for the U.S., it signals to foreign governments they no longer need to factor them in when engaging with the American government.

Rubio asserted that the U.S. would pivot away from supporting the ‘global order’ in favor of prioritizing its national interest. This is an interesting paradigm shift, because the global order that he disparages here was created to favor U.S. interests in the wake of the Second World War and then even more so after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The global setup in its current form, and the de facto rules based order in place, was cultivated by subsequent American administrations to amplify U.S. power around the world.

Whether through leveraging its influence in NATO to magnify its influence in Europe, or through enhancing its effective control over the Middle East with its critical resources and geostrategic position, or its effective engagement with Asia to manage the rise of China through its east Asian alliances, the U.S. ensured that its voice and presence was amplified through a solid network of partnerships and frameworks that cultivated dependency and therefore support.

Dismantling this order could prove to be the diametric opposite of pragmatism from a foreign policy perspective. It would provide U.S. rivals with an opportunity to construct their own alternative orders that favor their interests, and at the same time gradually relegate the U.S. to a powerful yet comparatively isolated actor on the international stage. Withdrawing from multilateralism, focusing exclusively on bilateralism, and reducing engagement with other countries to short term transactional engagements will fragment existing alliances and structures.

We are already seeing the manifestation of these potentialities, with China for example inserting itself into voids left by U.S. withdrawals from the World Health Organization and the Paris Accords, and Europe’s reassessment of its independence and global priorities.

Power Plays: Control Over Allies or Cooperation?

When questioned about the President’s position on Canada, Panama and Greenland, Rubio emphasized that U.S. national interests dictated Trump’s pivot against these three long standing American allies, and the way to address those interests, according to the Trumpian approach, is to take control of them.

On Panama, Rubio echoed Trump’s position that the canal should be under American control, because the U.S. built the canal and because it is a core national interest. He also reiterated the perceived slights of being unfairly treated -that have been since fact checked - by Panamanian government’s fees regime for crossing the canal, from which Trump believes the U.S. should be exempt.

Elaborating on the national security aspect of the Panama issue, he stated that China had all but gained effective control of the canal through its companies that operate Panama ports, and emphasized that anything short of full U.S. control of the canal would be an unacceptable risk for the American government.

The intrusion into the sovereignty of nations like Panama—despite long-standing agreements to safeguard U.S. interests—appears to hold little significance for the current administration. The two treaties in place between the U.S. and Panama, the Panama Canal Treaty and the Treaty on Permanent Neutrality, already provide significant guarantees for American concerns, but fail to assuage the U.S. administration’s apparent determination to seize it.

This tells us two main things. First, the foreign policy regime under Trump does not place stock in existing agreements or legal frameworks, and has no hesitation to violate them, whether under the guise of national security or otherwise, and that confrontational public engagement is entirely acceptable. Any embarrassment caused to other nations is seen as a small price for bolstering the image of American strength domestically. The second is that this administration is operating from the perspective of being threatened, and this is a recurrent theme that we will see in other decisions.

Applying this same perspective to Trump’s position on acquiring Greenland, we see similar patterns emerge. Trump and his administration, including the Secretary of State, have little faith in the security guarantees embodied by NATO, which Denmark and by extension Greenland is a founding member of, and through which the U.S, has secured active military presence on the island since 1951. In fact, prior to NATO’s founding, the U.S. had sought to take control of Greenland several times, most recently in 1946, but since the establishment of the transatlantic alliance, it considered its Artic security concerns well addressed through both its military presence and the strong commitment of its allies.

Yet the current administration, consistent in its distrust of multilateral frameworks, disregarded the security guarantees offered by NATO, and expressed the need for greater control. Operating again from a lens of vulnerability and the need for direct control separate from that offered by existing multilateral frameworks, Rubio stated that Greenland represented a national security concern. China, according to the Secretary of State, could realistically install facilities on the island from which it could pose a threat to the U.S. in the future.

When questioned about the role of Denmark and NATO in the defense of Greenland, Rubio stated that the U.S. would have to intervene, which led to the deeply concerning claim that since the U.S. was already “on the hook” to defend Greenland in case of a hypothetical attack, it might as well have more control.

This statement would give anyone looking to establish defense agreements with the U.S. pause. If other countries, like Saudi Arabia for example, were to look at this and apply it to their own position, they may reconsider the value of having a U.S. security umbrella. If the current administration considers defense pacts open invitations to seize control of another country’s territory in the interests of American national security, they may be more trouble than they are worth.

Rubio persisted that the Trump’s Greenland position is a serious one, and that while he would prefer to purchase it – something that Denmark and Greenland have both refused- he kept all options on the table for the way forward. In explaining the President’s reticence to rule out military acquisition of the territory, Rubio said that he did not want to remove any leverage from the negotiation. Rubio added that in four years, U.S. interests in the Arctic would be more secure, an ominous threat as far as Denmark and Greenland are concerned because accomplishing this goal seems intrinsically tied to acquiring the territory.

This position is an extension of the established pattern, taking the disdain of multilateralism a step further. NATO is unlike any other alliance for the U.S. and Europe, having served as the primary deterrent to Soviet expansion and as the bulwark of collective Western defense, the hard arm to supplement the economic influence the West accrued since the Second World War.

For American allies and partners around the world, this position in particular, more so than the administration’s position on Panama, was a jarring wake up call. The unprecedented threat from the U.S. toward a fellow NATO member conveys a stark message that no partnership or alliance is free from potential reconsideration.

This has already incentivized Europe to reconsider the value of its transatlantic alliance; if the greatest threats to member states of NATO comes from the U.S., then Europe has to develop its own systems of deterrence disconnected from the U.S., something that various European leaders have been advocating for some time.

Whether or not the U.S. carries out this threat, the mere consideration of its possibility without a direct impending threat from external adversaries has already fractured the trust built over decades of collaboration. While the public facing discourse will remain civil -at least until further escalation- behind the scenes Europe will likely be scrambling to redesign its collective defense and economic framework around continental rather than transatlantic priorities.

On Canada, the discourse was less aggressive, yet still problematic. Rather than dismiss the notion of Canada as a 51st state, as would be expected from an American Secretary of State, he leaned into the question by stating that Canada’s economic reliance -according to him- on the U.S. means that it would be better served by becoming a state than remaining independent. While more easily dismissed than the quasi-threats leveled at Panama and Greenland, the position remains tactless; it is one thing if a private citizen or a politician says it, it is quite another when the top diplomat of the country does.

All Policies Lead to China?

China has been a fixation of Rubio’s since throughout his political career, and his vocal stances on China resulted in his sanctioning by the Chinese government in 2020. During his senate days, he maintained that the outcome of the “conflict” -his word- with the Chinese Communist Party was the most important issue for America’s future. In his capacity as Secretary of State he is more restrained than he was as a senator, when he referred to China as a “brutal, authoritarian police state.”

Rubio voiced concerns over China’s expanding global reach, labeling it a great power rather than a developing nation. He referenced its growing footprint and control over mining for materials around the world, and the unfairness of its tactics on the global stage, while admitting that it was operating in its own national interests when doing so, adding that the history of the 21st century would revolve largely around the interactions between China and the U.S.

Throughout the interview, whether he was discussing Panama, Greenland or U.S. engagements around the world, he brought the conversation back to China. The Trump administration’s approach to its Asian rival are framed as a zero sum game, if China rises, according to Rubio, it must do so at America’s expense.

The elevated level of concern about its growing influence reverberates throughout the conversation; its influence on Panama, its potential access to Greenland, its control over mining and natural resources around the world, its impact on the Global supply chain, and its growing geopolitical weight.

The reaction to China however may be conveying an unintended message: the U.S. is intimidated by China. Though U.S. worries over China’s expanding influence are valid, Rubio seemed to overstate American vulnerability while downplaying U.S. power. The approach appears reactive and rushed, rather than calculated and deliberate; instead of building upon existing frameworks designed to amplify U.S influence, this administration seems intent on self-isolation and confrontation.

This is almost a diametric opposite of the approach that China is adopting. While the Trump administration is apparently intent on alienating even its closest allies, China is building a broad base of alliances and partnerships around the world. It is leveraging its influence in the Global South through blocs like BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and filling in gaps left by the U.S. as it withdraws from multilateral frameworks like the WHO and the Paris Agreements.

As the U.S. increasingly adopts its confrontational approach under Trump, we can expect China to pursue a more placating tone with international actors, providing an alternative to an increasingly problematic and potentially unreliable American partner. Despite the strong position on China, however Rubio also indicated awareness that both countries, as the greatest global powers, had a joint responsibility to avoid escalation.

It is somewhat ironic that the administration would approach the dynamic with China in this manner. Avoiding direct escalation due to the risks involved for both sides, economic and otherwise, while engaging in unnecessary escalation with close allies under the pretext of preempting China’s interests with them, rather than rallying them under the banner of joint interests.

From this, we infer that China is going to be the issue that dictates U.S. foreign policy for the next four years, but the ways the policies manifest may not be what we expect. If you had told me one year ago that the U.S. would attempt to contain China by threatening to invade a fellow NATO country, I would not have believed you.

NATO’s Fragile Future: Realignment or Rupture?

Rubio accused NATO members of not doing enough to provide for their own security, lamenting the fact that rich western European states were content to rely on the U.S. security umbrella, fostering a dependence rather than an alliance. In this he was not entirely wrong, because Europe has developed a pattern of over reliance on the U.S. for its security and has therefore become increasingly drawn into its orbit.

Where he was mistaken however is that he stated that this was not in U.S. interests; European dependence on the U.S. is a feature, not a bug. Successive U.S. governments nurtured this dependency and over reliance because it provides ample leverage and influence in the continent. The most recent and visible example is in the Russo-Ukraine war, where the U.S. essentially maneuvered Europe to its position vis-à-vis Russia, undoing a decade of German balancing between the U.S. and Russia on the continent.

This action was a strategic masterstroke on the part of the Biden administration. In one swoop, it convinced Europe to sever its ties to Russia, align with U.S. foreign policy objectives, and substitute Russian natural gas with U.S. liquified natural gas, fostering both increased security and energy dependence on the U.S.

Rubio, under Trump’s leadership, appears more aligned with the Eurocentric view of Europe, where European reliance on the U.S. is reduced and the partnership takes on a more equitable form. This departure from the current NATO dynamic, which would result in greater European foreign policy independence, would possibly cause a divergence of interests between members of the alliance. Whereas the U.S. could currently leverage European dependence to rally its support for policies abroad, it would no longer be able to do so, effectively reducing American influence in one of its key strategic areas.

Had Europe been less reliant on the U.S. in 2021, the Russia-Ukraine war may have never occurred, for example, and the U.S. goals of weakening Russia over the medium to long term and studying its military strategies and equipment may have not have been achieved.

The dismissal of NATO, coupled with threats toward Greenland, has left Europe questioning the stability of its transatlantic alliance, revealing deep fractures in mutual trust. Whether these ties will be repaired through a more collaborative rather than combative approach over the course of the administration’s term will determine the balance of power on the international stage for years to come.

Exit Strategy? Washington’s New Position on Ukraine

One of President Trump’s campaign promises was a swift end to the Russo-Ukraine war. He, and many of his supporters in the Republican party, are opposed to U.S. involvement in conflicts abroad whether directly or financially. As a result, ending this war has become a policy priority for the Department of State.

Rubio stated that there has been some dishonesty on the potential outcomes of this war, which he views as protracted and needing to end. Both sides, he added, will have to make some concessions, including some territorial concessions on the part of Ukraine. In his view, the U.S. is and has been funding a stalemate and Ukraine is losing more as the war progresses, and neither side will at the end achieve its maximalist outcomes.

In framing it in those terms, Rubio conveys a few interesting messages, including that he -and therefore Trump- sees that time is in Russia’s favor. It also indicates that the U.S. will not continue to fund Ukraine indefinitely, effectively pressuring it to seek compromise to end the war.

He also may have inadvertently signaled that the U.S. is not a reliable partner. Ukraine relied on U.S. and European backing since the outbreak of the war, and to be left to its own resources this deep into the conflict would leave it at Russia’s mercy. Other U.S. allies and partners will be looking at this and taking notes: would they too, if they relied on U.S. support, find themselves left to fend for themselves if U.S. administrations shifted positions?

This is an important question for other actors around the world that have invested in their alliance with the U.S.. If the American government could so easily divert its policy positions regardless of the precarious position of its partners, what would stop it from doing so again in the future? This may incentivize other allies to hedge their bets through balancing great power dynamics with other global actors to reduce reliance on the U.S., a pattern which could gradually reduce American global influence.

The Middle East: A Familiar Policy in a Sea of Disruption

On this portfolio, Rubio’s responses fell in line with long term American policy for the most part. He reiterated strong U.S. support for Israel, and the necessity of ending Hamas’s presence in Gaza, and stated that there was a lot of work to be done on the Palestinian question, without making any reference to the two-state solution long upheld by U.S. governments.

He praised Trump’s success in negotiating the Abraham Accords -a series of normalization agreements between Israel and several Arab Nations brokered by the U.S.- during his first term. He then expressed hopes for the achievement of the Saudi Arabia normalization deal with Israel, which is contingent on the establishment of a Palestinian state, and cautiously welcomed the change in government in Syria. With reduced Russian and Iranian influence, and a more stable Lebanon under its new government, the region is poised to move in a different direction.

He carefully avoided making any references to President Trump’s statements about relocating Palestinians to Egypt and Jordan, which caused considerable backlash not only from the three countries, but also from several other important actors in the region -including Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates, all key U.S. regional allies.

A Blueprint for Disruption: The New U.S. Foreign Policy

This interview provides a remarkable blueprint for the new administration’s modus operandi on foreign policy—a paradigm shift of gargantuan proportions. Rubio’s messaging, echoing Trump’s vision, makes it clear: the approach will be purposely disruptive, adversarial, and deeply transactional.

Barely two weeks into this new term, the foundations of long-standing alliances have already been shaken, raising pressing questions about global stability and the future of U.S. diplomacy. NATO partners are on edge, allies are recalibrating their strategic positions, and rivals are watching closely, waiting for opportunities to fill the voids left by U.S. retrenchment.

Yet, beyond the immediate chaos, a larger transformation is unfolding. The administration’s rejection of traditional multilateralism, its preference for direct control over diplomatic engagement, and its willingness to override decades of precedent in favor of unilateral decision-making mark a fundamental shift in America’s global role. The U.S. is no longer positioning itself as a stabilizing force within the international order but rather as a power willing to challenge, dismantle, or outright disregard that order if it does not serve immediate national interests.

This is a foreign policy of calculated volatility, one that forces allies, rivals, and international institutions to either adapt to Washington’s new doctrine or risk being left behind. Whether this strategy will yield long-term gains or further isolate the U.S. on the world stage remains to be seen. What is certain, however, is that U.S. diplomacy is no longer operating under the old playbook—and every global actor must now navigate a far more unpredictable landscape.